Back to What You Love

Interventional Pain Medicine Procedures

Steroids are potent anti-inflammatory medications. The goal of an epidural steroid injection is to place this medication near the area of injury or pathology within the spine. The steroid medication reverses the effect of pain-producing inflammatory compounds produced by the body, thereby easing pain and allowing for improved function. A local anesthetic is usually injected with the steroid, which may provide immediate short-term pain relief. By combining a local anesthetic and steroid, diagnostic information may be obtained in addition to the provision of therapeutic relief. The most common use of epidural steroid injection is for spinal nerve irritation, commonly referred to as radiculopathy or, in the lower back, as sciatica. Epidural injections are also commonly used to treat intervertebral disc pain, spinal arthritis, spinal fractures, post-surgical pain, tumor-related inflammation and post-herpetic neuralgia. The injections can be performed on any level of the spine. Three distinct techniques are commonly used and are described below.

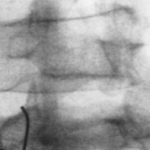

In this technique, an x-ray (fluoroscopy) is used to guide a needle into the posterior epidural space. The injectionist “feels” a change in resistance to determine the correct needle depth and the correct needle position is confirmed by x-ray imaging of injected contrast solution. The major drawback of the interlaminar approach is the deposition of medication into the posterior (back) area of the spinal canal, while most pathology is located in the anterior (front) part of the canal. With large volumes, 5 to 10 cc’s of solution, the medication usually spreads to both the front and the back of the canal. Therefore, with diffuse disease processes involving several spinal levels or disease processes involving structures in the posterior spinal canal, the interlaminar technique is a reasonable approach.

This technique represents a very precise, x-ray controlled injection of a small volume of medication into the anterior epidural space and the exiting spinal nerve sheath. It is a useful technique for precisely diagnosing the specific level of pain generation, as well as treating pain of disc or spinal nerve origin. When making a diagnosis, the suspected areas of pain generation are located on x-ray and a small needle is placed into each neural foramen (the spinal opening through which the spinal nerve exits). Each needle is then injected with a small amount of contrast and the appropriate spinal nerve and proximal epidural space is observed on the x-ray monitor. The resulting contrast spread, called an epidurogram, can give valuable information regarding the anatomy at the injected level. Additionally, the patient may feel a paresthesia, or tingling sensation, in the area of the body supplied by the injected spinal nerve. If this paresthesia is in the same location as the patient’s pain, it can be deduced that this spinal nerve is contributing to the patient’s pain symptoms. Furthermore, the injection of a small amount of local anesthetic should eliminate the pain for a short time, further supporting the diagnosis. The injected steroid acts to decrease inflammation at the specific area of injection, thereby providing analgesia and allowing for increased function. Several studies have confirmed that transforaminal epidural steroid injections are highly effective in treating radicular pain and can prevent surgery in two-thirds of patients.

This is a technique that accesses the epidural space near the tailbone. It is used for pathology in the lower spine, such as pain in the coccyx or tailbone, or to atraumatically access the epidural space in the patient with low back pain and a history of previous lumbar surgery. By entering below the area of previous surgery, scars and surgically altered anatomy can be avoided. This is performed with X-ray guidance and contrast injection to assure correct needle placement. Typically, relatively large volumes of medication are injected into the caudal space, ten to fifteen cc\’s, to assure that the medication reaches the areas of pathology. Another advantage to the caudal approach is the tendency for the injected medication to pass into the anterior epidural space, the area adjacent to the spinal nerves and discs.

The zygapophysial joints, also called the facet joints, are common sources of pain, either from degenerative arthritic conditions or from acute injury. The pain typically occurs with twisting or backward movements of the spine. In the neck, zygapophysial joint pathology may be associated with headaches, shoulder pain or upper back pain and, in the lower back, these joints may cause back, buttock or thigh pain. These joints are located in the posterior area of the spine and are accessed for injection with the use of X-ray imaging. Two injection techniques are used to treat zygapophysial joint-related pain and each is described below.

In an intraarticular zygapophysial injection, the joint itself is penetrated with a needle and a small amount of contrast is injected, confirming correct needle placement. Then, a combination of local anesthetic and steroid is injected. The effect of the local anesthetic may confirm the joint as a source of pain and the steroid may act to decrease inflammation for long-term relief. In some cases the injected steroid may have excellent long-term results.

In a medial branch injection, the two small nerves that supply each zygapophysial joint are blocked with a very small amount of local anesthetic, effectively decreasing the ability of the joint to generate sensation of pain. This injection is diagnostic. Therapeutic intraarticular injections may follow or the patient may undergo radiofrequency neuroablation. In this latter technique, a special needle is used to supply electrical energy to the nerves supplying the previously “blocked” zygapophysial joints, resulting in long-lasting pain relief. Radiofrequency neuroablation demands very precise needle placement and a rigorous protocol to maximize efficacy and assure that motor or sensory nerves are not damaged. Please refer to the section below.

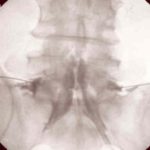

The sacroiliac joints, or SI joints, exist on both sides of the lower back, joining the spine to the pelvis. These joints are susceptible to injury, either by chronic stress or acute injury. This type of pain may occur with other spine problems and the diagnosis of sacroiliac arthropathy is frequently overlooked. The joint is injected with local anesthetic and steroid under X-ray guidance. Typically, this is a difficult joint to inject and requires precision needle placement and confirmation of correct placement by documentation of appropriate contrast spread. Injections may be repeated multiple times to effect long-term relief. Best results occur when the injections are performed in coordination with physical therapy.

This technique is used to diagnose discogenic pain, pain generated from the intervertebral disc. This technique is properly termed “provocation” or “provocative” discography as the disc is stimulated in an attempt to reproduce clinical pain. This study attempts to reproduce internal disc pressures, similar to pressures generated in painful activities, in order to diagnose disc pain. A normal disc accepts the injection of contrast without pain, usually maintains a high internal pressure with the injection, and demonstrates no leak of contrast from the central portion of the disc. The injection of an abnormal disc will cause pain similar to the patient’s symptoms at a relatively low internal pressure, and may demonstrate an abnormal pattern of contrast spread. A CT obtained immediately after the discogram will delineate the internal anatomy of the disc. Therefore, discography, when performed correctly and according to protocol, can generate information about pain physiology as well as internal disc anatomy.

Disc stimulation is not a therapeutic technique. It is designed to make a diagnosis. The consequences of positive discography may include major surgery or other interventions and, therefore, it is imperative that this procedure be performed with the utmost attention to detail. Several studies have demonstrated the inaccuracy of this procedure if performed on patients without appropriate pain or with psychological illness. Therefore, logic dictates that disc stimulation should only be performed on patients who have clinical pain consistent with disc pathology and who have no psychological disease.

Is a new technique that offers promise for specific back pain patients with positive disc stimulation, an intact annulus and the desire to avoid surgical intervention. In this procedure, a mixture of dextrose, chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine are injected into the nucleus. The concept is that these medications stimulate regeneration of the disc annulus, thereby increasing structural integrity and relieving pain. Studies are ongoing regarding this therapy.

As referred to above in the section regarding zygapophysial joint injections, thermal energy can be used to selectively destroy specific sensory nerves that are involved in the transmission of pain. Most commonly, the small nerves to the zygapophysial joints are subjected to this procedure. This technique may also be used to treat the thoracic splanchnic nerves for abdominal pain. Because the procedure physically damages the targeted nerves, the physician must take great care in properly placing the needles. Prior to the radiofrequency procedure, it is important that a separate injection procedure be performed with local anesthetic, thereby establishing the diagnosis that will predict the effectiveness of the neuroablation. When performed properly and selectively, this can be a very safe and effective pain relief technique.

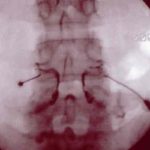

In this procedure, one or two wires (leads) are placed into the epidural space to provide electrical stimulation of the spinal cord, acting to interfere with the transmission of pain. This technique is very effective in arm and leg pain caused by nerve injuries and can also be useful in some types of low back pain. It has also been used to treat pain from vascular insufficiency and chest pain. The stimulation can be adjusted by the patient, thereby adding an element of personal control over the treatment of pain.

The leads are surgically implanted. Prior to such surgery, a trial is performed. During this trial, the leads are placed through the skin without an incision and attached to an external power supply worn on the patient’s belt. The patient may then go home and use the devise for several days to determine effectiveness. Permanent implant is considered only if the trial decreases the patient’s pain over 50% and improves function.

The permanent implant may consist of thin leads or larger flat paddle leads. The latter requires a more extensive surgical procedure called a laminotomy but provides more efficient energy output, less chance of movement and more extensive coverage. The thin leads require less invasive surgery but have an increased tendency to change position. In addition, the generator or power supply can either be implanted or worn externally. The decision regarding the type of permanent implant to be used is made on an individual basis, based on the pattern of the patient’s pain, the results of the trial stimulation, and the patient’s preference.

Many medications that are normally given by mouth or intravenously can be delivered directly into the spinal canal. The advantage of this delivery is that a much smaller dosages of medication can be used, thereby minimizing many side effects associated with other oral or intravenous use. Typically, the intraspinal administration is 300 to 1000 times more effective than the oral dose.

Morphine (and other opioids or narcotics) interacts with opioid receptors in the spinal cord to decrease pain impulses to the brain, thereby decreasing the brain’s perception of painful conditions. While developed for cancer pain, the intraspinal use of this medication has proven very effective in chronic benign (non-cancer) pain as well. Intraspinal delivery may allow the patient to significantly decrease the amount of oral medications ingested, thereby decreasing side effects. Because the effectiveness of intraspinal morphine is many-times the effectiveness of oral morphine, the patient’s pain relief may allow resumption of a much more active lifestyle.

Prior to the implantation of the pump and catheter, a trial procedure is performed which demonstrates the effectiveness of the medication for the particular patient. The implantation requires a surgical operation and an anesthetic.

The sympathetic nervous system may be involved in specific pain syndromes. These include complex regional pain syndrome (formerly called reflex sympathetic dystrophy or RSD), atypical facial pain and microvascular ischemia. Local anesthetic injected around the sympathetic ganglia in the cervical or lumbar spine may diagnose sympathetic involvement in painful conditions of the head/neck/upper extremities and the lower extremities, respectively. These procedures require the use of X-ray at a surgery center in order to provide accurate needle placement and treatment of potential side-effects. The patient is evaluated immediately after such injections in order to determine the effect of the local anesthetic.

For certain conditions, repeated sympathetic nerve blocks combined with aggressive physical therapy can result in symptom resolution.

For recalcitrant conditions, long-term block of the sympathetic nervous system can be obtained by radiofrequency neuroablation or spinal cord stimulation.

Abdominal and pelvic pain is mediated by nerves that coalesce with specific ganglia near the lumbar spine. The well-defined location of these ganglia allow for interventions designed to alleviate chronic abdominal or pelvic pain.

Abdominal pain may be treated with a celiac plexus axis intervention. The celiac plexus is located just anterior to the aorta at the L1 vertebral level. For malignant pain such as pancreatic, stomach or liver cancer, this intervention may consist of the precise injection of alcohol which destroys the nerves that mediate pain. This is a precise injection that requires X-ray localization and intense post-procedure monitoring and treatment of side-effects. Prior to the neurolytic block, a diagnostic block with local anesthetic is usually performed in order to demonstrate efficacy of the technique and lack of serious complications. For benign pain conditions that demonstrate short-term improvement with local anesthetic celiac plexus block, radiofrequency neuroablation of the bilateral greater and lesser splanchnic nerves may be performed. This splanchnic nerve procedure may be repeated indefinitely, typically at six to twenty-four month intervals.

Pelvic pain is mediated through the superior hypgastric plexus which is located anterior the spine at the L5-S1 vertebral level. Again, this injection requires X-ray guidance at an ambulatory surgery center as well as a diagnostic block with local anesthetic prior to using alcohol for neuroablation. Because this procedure may have negative side-effects involving bowel and bladder function, the neurolytic procedure is usually limited to malignancies involving the pelvic organs.

Occasionally, a specific muscle may generate pain due to sustained contraction and subsequent localized ischemia. While this type of pain is usually secondary to another problem, it can occur primarily. These areas of muscle pain are called trigger points and can be treated with injection of small amounts of local anesthetic solution with or without steroid, usually in concert with specific physical therapy treatments. If the primary source of the muscle pain, such as an arthritic zygapophysial joint, is identified, then it is important to treat this primary pain source as well. Trigger point injections are usually performed in the office. Some deep muscle injections, such as the piriformis and iliopsoas muscles, are performed under fluoroscopy.

It is not uncommon for specific joints to cause debilitating pain, either due to acute injuries or chronic arthritis. As a pain-alleviating treatment to delay eventual surgery or to augment physical therapy, injections of local anesthetic and steroid may be performed into or around specific joints. Common joints include the shoulder, knee and hip. These injections may be performed in the office or, if fluoroscopy is indicated, in an ambulatory surgery center.

Certain conditions such as tennis elbow (lateral epicondylitis), golfer’s elbow (medial epidcondylitis), carpal tunnel syndrome and other tendonopathies may benefit from localized injection of anesthetic and steroid. Also, certain peripheral neuropathies may respond to injections around the involved nerves. These injections are only performed if more conservative treatments fail and judicious amounts of medication are used. Typically, these procedures are performed in the office.

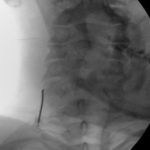

This technique used to treat low back and or lower extremity pain caused by lumbar spinal stenosis-the squeezing of the nerves inside the lower spinal canal. Instead of open surgery with hospitalization and a prolonged recovery, this procedure is done in an outpatient surgery center, requires only local anesthesia and is performed with only two or four small incisions that require no stitches. Under X-ray guidance (using a fluoroscope), a small tube is placed into the spinal canal outside the epidural space. Through this tube, instruments are placed that are used to remove a small amount of ligamentous tissue from the posterior part of the spinal canal. This reduces compression on the nerves within the spinal canal and, in approximately 50% of patients, eliminates pain. There is no recovery time and the pain relief is typically immediate. Like all procedures, the indications are very specific: MRI or CT documented spinal stenosis with enlargement of the ligamentum flavum and neuroclaudication symptoms (pain in the low back and/or lower extremities with standing and walking).

The Vertiflex Procedure is redefining the treatment of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis (LSS) for patients. It provides patients with a clinically proven, minimally invasive solution that is designed to deliver long-term relief from the leg and back pain associated with LSS. This level-one evidence-based procedure is supported by data from patients who reported successful outcomes up to five years.

Leg and back pain may be the result of a condition called lumbar spinal stenosis. LSS leads to the narrowing of the space in the lower (or lumbar) spine where nerves pass through. The narrowing of the space causes constriction on the nerves, which may result in pain and discomfort down the back and into the legs.

Pain is usually worsened when standing or walking, and leaning forward or sitting down provides relief. For most people, LSS develops gradually over time and is most common in adults over the age of 60.

Contact Us

Location

9159 W Flamingo Rd, Suite 100 | Las Vegas, NV 89147

Business Hours

8.00am – 5.00pm (Monday – Thursday)

Call or Fax

Office: (702) 307-7700 | Fax: 702 307-7942